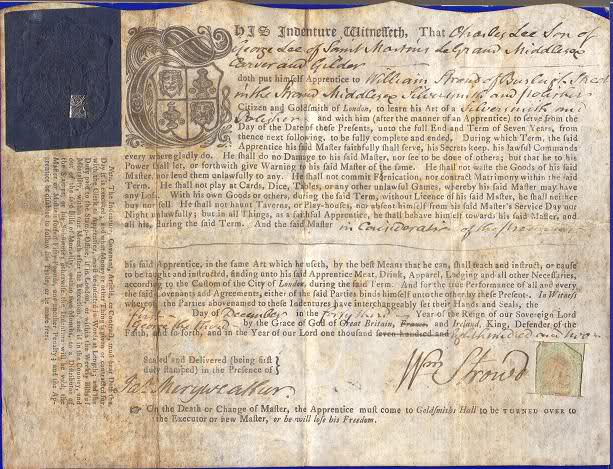

Detail from Indenture illustrated below

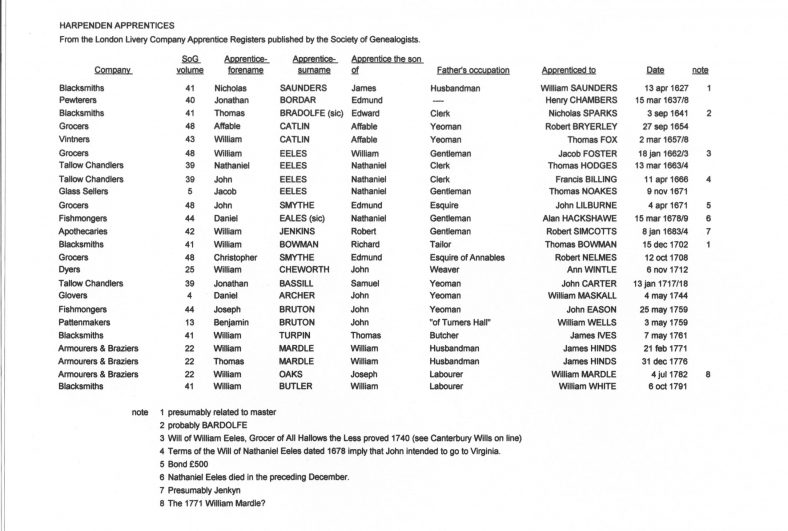

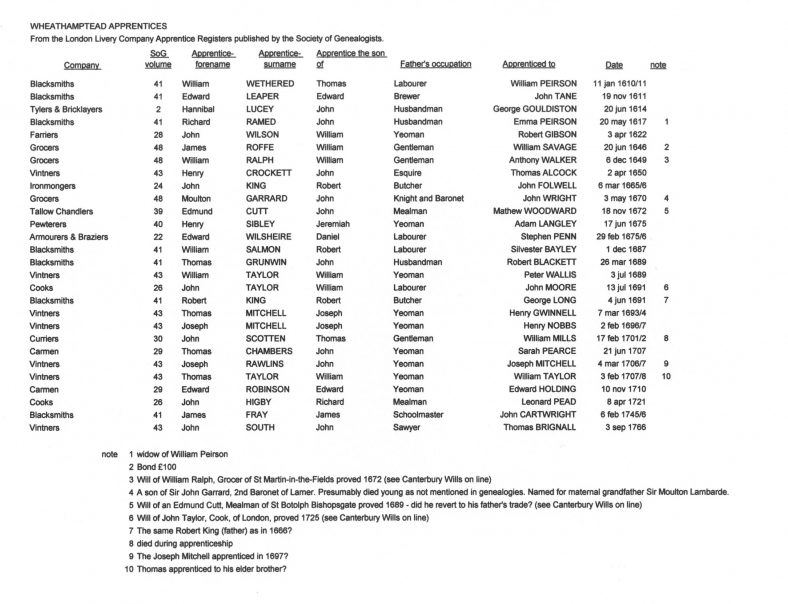

The attached lists (1) of apprentices from Harpenden and Wheathampstead who were apprenticed to London Livery Companies in the 17th and 18th centuries were extracted from the summaries of London Livery Company Apprenticeship Registers published by the Society of Genealogists. The actual dates covered vary from Company to Company, commencing in the early seventeeth century and ending around 1800. The earliest local apprenticeship was in 1611 and the last in 1791.

Currently there are 48 volumes covering most of the Companies in existence at the time. However the list is not exhaustive as some Companies, especially the Goldsmiths and Haberdashers, are not included. These lists were compiled by Cliff Webb from surviving records. They are very well indexed which facilitates searches by apprentice name, master’s name and County and place of origin.

All apprentices from Harpenden and Wheathampstead found in the 48 volumes have been listed in separate tables in date order.

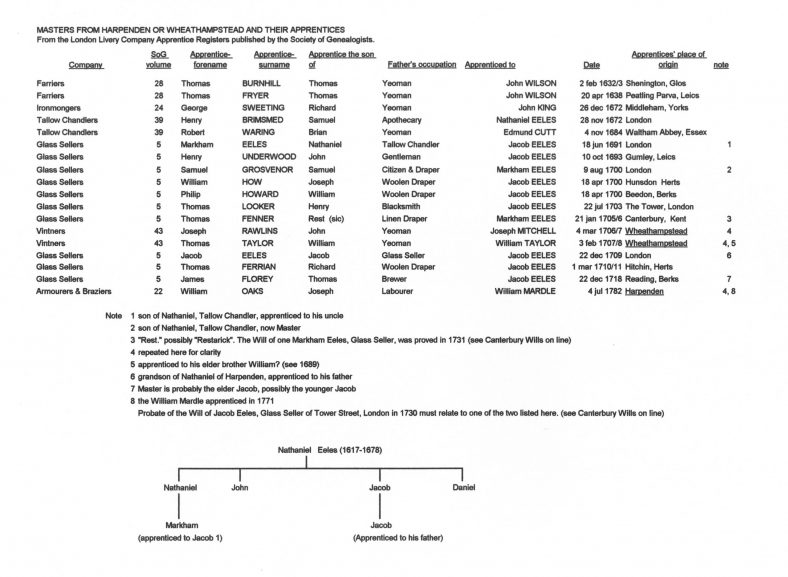

A third table lists those Harpenden and Wheathampstead apprentices who subsequently took on apprentices themselves, again in date order. Three of them took on an apprentice from their parish of origin and so appear in both lists.

No ages are given but it is probable that most apprentices were indentured at about 14. There are three cases where apprentices were bound to widows carrying on their husband’s crafts. Only one apprentice is noted as having died during the apprenticeship, which implies a remarkable survival rate for these new arrivals in London. The small number who subsequently became masters themselves and took on apprentices suggests a higher mortality rate although some may not have completed the apprenticeship or did not go into business for other reasons. Any master who did not take on any apprentices would not appear here.

Why become an Apprentice?

The outcome of a successful apprenticeship was to be granted the status of Freeman of the City of London which allowed residence and the right to trade in the City in any permitted business, not just that of his Company. Edmund Cutt appears to be one such – apprenticed to a Tallow Chandler but trading as a Mealman, his father’s trade. Not all apprentices actually served their indenture. It was possible to become a Freeman of the City of London by “redemption”, or purchase, so some listed may have become “free” by this means. The son of a Freeman could also claim the Freedom of the City by “patrimony” or birth.

Some of the wealthiest local families had made money in London, either in trade or in the service of the State, such as Witteronge, Garrard, Cotton, Smythe and Stubbing. The period covered saw further incomers from London, or at least buyers of property, such as the Farringtons (the law) and the Ashbys (Haberdashers) so the benefits of success in London were apparent to the local population.

However a total of 55 indentures in 180 years is not a significant movement to the Capital. Of the 55 indentured, 31 were in the 60 years from 1660 to 1720, after which the rate falls away. As it is not known what proportion this was of the relevant male population or how many other local boys were apprenticed to masters outside London in the period, the list is too small for meaningful statistical analysis.

Putting in a good word (“it’s not what you know…”)

The connections that led to the apprenticeships are not known apart from the few direct family relationships. Nathaniel Eeles was ousted from his living as Rector of Harpenden after the Restoration. As both Sir John Witteronge and Sir John Garrard had been supporters of Parliament and in agreement with Eeles in matters religious, their London connections may well have aided Eeles in apprenticing four of his sons. Two of them took apprentices themselves, with Jacob Eeles taking both his own son and his nephew.

The only connection I can infer as a result of other researches is that of Thomas Grunwin to Robert Blackett. The link could have been one William Bursey, Coachmaker, of the Parish of St. Sepulchres in London. His son married the daughter of Robert Blackett, Blacksmith, of St. Sepulchres. They were old friends; in 1669 Blackett was one of the witnesses to Bursey’s sale of a cottage in Harpenden to Joseph Lines, also a Blacksmith! (Newsletter 103 p20)

Bursey held freehold and copyhold lands in both Harpenden and Wheathampstead parishes and had acquired about 40 acres of copyhold land from one branch of the Grunwin family in the 1660’s. In 1680 Bursey appears to have bought land from another branch, the Grunwins of “The Hill”, Wheathampstead by means of a legal device, a Fine or Final Concord. These Grunwins were the grandfather and father of Thomas the apprentice. “The Hill” being the farm of that name on Plummers Lane. From surviving papers the matter appears more complex than the usual procedure but it was apparently settled amicably.

Bursey (c1630 – 1686), like Cutt, traded in a business other than that of his nominal Company. He was a Coachmaker (a few of his bills survive) but was a Freeman by membership of the Mason’s Company. Until 1677 he described himself as “citizen and free mason of London” but when the Coachmakers and Coach Harness Makers Company was incorporated in that year (with Bursey as the first Master of the Company) he became “citizen and coachmaker”.

The above notes were compiled in part from ongoing research. Please contact the Editor if detailed references are of interest.

(1) The lists can be viewed in a larger format by opening the downloadable Excel documents at the very bottom of this page.

HARPENDEN

WHEATHAMPSTEAD

MASTERS FROM HARPENDEN & WHEATHAMPSTEAD and EELES relationships

A typical apprenticeship indenture: Charles Lee, son of George Lee of St. Martins Le Grand, Middlesex, Carver and Gilder, as apprentice Silversmith and Polisher to William Stroud, Silversmith and Polisher of Burleigh Street in the Strand. Stroud was a Freeman of the Goldsmiths’ Company (“Citizen and Goldsmith”). The document is dated 1802 – note the frugal use of a printed form from the previous century.

Comments about this page

Thank you! This has been very helpful in my research into the Eeles family.

That’s just what we hope by putting things on the website! Ed

Add a comment about this page