This page was first published in the Society’s Newsletter 136, December 2018

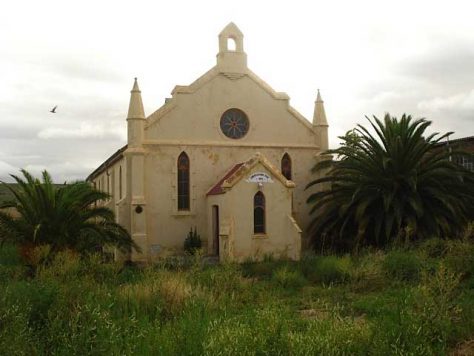

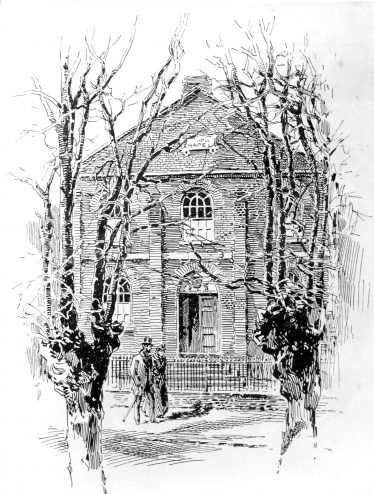

Independent Chapel – former Congregational Chapel, Cradock. Credit: Roger Fisher c2012

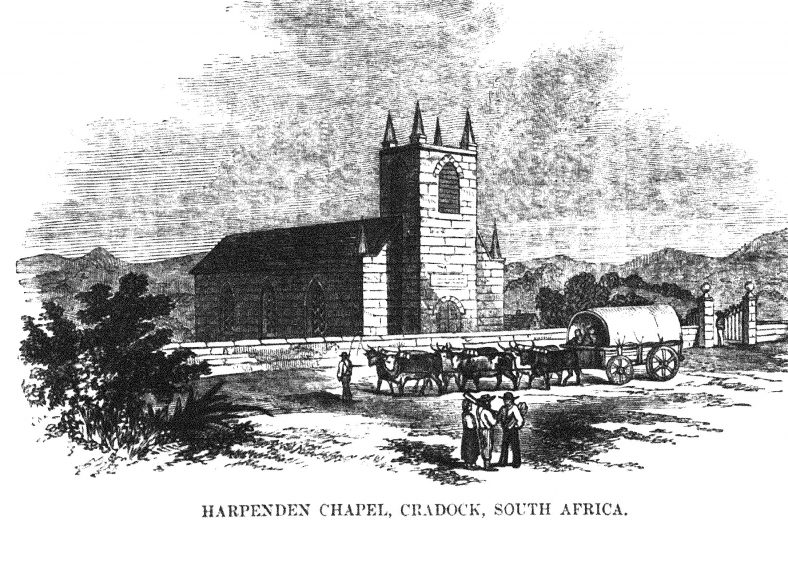

The article and engraving reproduced below were published in the London Missionary Society’s ‘The Missionary Magazine and Chronicle’, October 1853, Vol XVII. This volume has been scanned and reproduced online with no indication as to copyright ownership.

The article is transcribed and uses a modern typeface for clarity. The original punctuation and highlights have been retained. The engraving’s title is faint as ‘contrast’ has been adjusted to reveal the side window detail.

Engraving of Harpenden Chapel. Credit: The Missionary Magazine & Chronicle, Oct. 1853

SOUTH AFRICA. CRADOCK.

FRUITS OF NATIVE ZEAL AND INDUSTRY.

“HARPENDEN Chapel, from which the accompanying Engraving is taken, is situated in the town of Cradock, on a piece of land adjoining the Natives’ village, granted by Government. It fronts the approach to the town by the Graham’s Town road, is built of brick, upon a firm foundation of stone six feet deep, and is plastered within and without. It is fifty-seven feet in length, exclusive of the porch and tower, and twenty-two in breadth, and is designed to be furnished with a bell so soon as circumstances will permit.

“It bears the name Harpenden, both out of gratitude to Christian friends under the pastoral care of the Rev. G. B. Johnson, of the town of that name in Hertfordshire, who have been steady and liberal benefactors to the cause at Cradock, and also out of respect to the late Frederick Smith Esq., to whose family the Missionary is greatly indebted, both for many personal favours and for having originated the connexion between Cradock and Harpenden.

Memorial to Rev R B Taylor, to the left of the chancel. Credit: Roger Fisher c2012

“Connected with the erection of Harpenden Chapel are several circumstances which, while investing it with peculiar interest to the Missionary, the Rev. R. B. Taylor, and his people, may not be uninteresting to Christians in Britain.

“The Chapel has been ‘built in troublous times’, at a time when the whole eastern frontier of the colony and some parts of the west were ringing with the reputed worthlessness of ‘the coloured classes’, and the utter uselessness of attempting to bring them under the influence of Christian principles – when the London Missionary Society was being held up as the abettor and teacher of rebellion – when the feeling of hostility to the Society was so strong at Cradock, among a large portion of its inhabitants, that bullets were not unfrequently dropped into the collection plates – when its agent was being daily traduced as ‘a rebel at heart’, his footsteps tracked, and all his movements closely watched – when the natives under his care were liable to be insulted and threatened, and his dwelling to be forcibly entered at any hour of the day or night – and when the state of feeling which such things indicate was deemed honourable and the passport to public favour; – it was at such a time that the maligned natives were busily and quietly engaged either in making or burning bricks for their Chapel or in raising the superstructure, and thus giving one of the best refutations possible to the calumnies that had been heaped upon them.

Interior of Harpenden Chapel. Credit: Roger Fisher c2012

“It has been built almost entirely by the natives, and chiefly by their own subscriptions. With the exception of the carpenters’ work, the whole structure, from foundation to pinnacle, was raised by members of the coloured congregation, after a plan supplied by their Missionary; and with the exception of some three or four pounds subscribed by European friends in Cradock, and a small loan from the London Missionary Society, the expense of timber, &c. &c., has been met by subscriptions among themselves. The whole of the stone and of the brick-work has been done by the native Deacon and his brother, and who have not only given their time and labour throughout gratuitously, but have subscribed most liberally for the purchase of materials and for the hire of wagon and oxen, &c.

“Some persons, indeed, have affected to sneer at the structure, saying, ‘Oh, it is good enough for black people!’ but others, more candid and liberal, have acknowledged ‘they never could have thought such a building could have been erected by black people,’ and have spoken of its appearance in high terms.

“It has been presented to the London Missionary Society, and almost without debt. As a present, it is a meet but pleasing testimony of affection and gratitude to the honoured society by which the presentees have been supplied with the means of Christian instruction. The sum of £30 will have to be liquidated, but which the people hope in time to accomplish. Meanwhile the Missionary cherishes the hope that some kind, generous friends will be found in Britain willing to lend a helping hand, seeing it is to aid a people who have given practical demonstration that they are willing to help themselves, and that during a time of no ordinary trial.”

Building the Harpenden Chapel

Cradock, in Cape Province, some 160 miles inland from Port Elizabeth, was founded after Lt. General John Francis Cradock (the first British Governor of the Cape Colony) sanctioned expenditure on the first public buildings in 1814. The first settlers promptly named the settlement after him. The first church built was for the Dutch Reformed Church and was consecrated in 1817. It lies in what became the centre of Cradock, a few hundred yards west of the site of the Harpenden Chapel.

The first minister was the Rev. John Taylor, who was sent by the London Missionary Society (LMS). It was common for ministers sent by the LMS to ‘transfer’ to the Dutch Reformed Church. In 1826 Taylor had baptised Paulus Kruger, the future president of the short-lived South African Republic. John Taylor is erroneously credited as the builder of the Harpenden Chapel in some accounts. The actual motivating force was the Rev. Robert Barry Taylor, the R.B. Taylor named in the article.

Robert Barry Taylor (1810-1876) had previously ministered to freed slaves in the West Indies and he and his second wife, Marianne, were sent to Cradock by the LMS in 1848 to minister to the native population. They had married at Camberwell in 1840.

The Harpenden Chapel was built at the eastern end of what became the main street of Cradock and lay a short distance from the Great Fish River. The modern appearance differs from the original as, not long after construction, the river flooded and damaged the building. Sources give different dates for this flood but it was probably during the mid-1860s. It seems that major repairs were required and further works were carried out in the early 20th century but the basic design remained, although the original tower was removed.

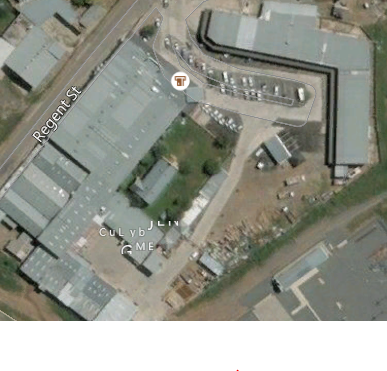

Cradock chapel, set in a green park amidst shopping centre. Credit: Google Earth

The ‘satellite’ view on Google earth shows a porched entrance on the far side of the Chapel but it is not known if this was an original feature. This porch is not visible in the photos on the website reproduced below but the entry door can be seen in one photograph.

Over time the name ‘Harpenden Chapel’ fell out of use and the chapel became a United Congregational Church. Some accounts state that both Robert and Marianne were buried under the pulpit but there is no mention of this on the memorial tablet in the church.

Congregational Chapel, Cradock, abutted by a modern shopping centre. Credit: Roger Fisher c2012

http://www.artefacts.co.za/main/Buildings/bldgframes.php?bldgid=7989

(wherein the Rev. John Taylor is confused with the Rev. Robert Barry Taylor)

The London Missionary Society and Frederick Smith

The London Missionary Society (LMS) was founded in 1795 by evangelical anglicans and nonconformists. Well-known missionaries in later years included David Livingstone and Eric Liddell.

The ‘late Frederick Smith’ mentioned in the article was a director of the LMS and was its chairman 1836-1844. He lived at The Terrace, Camberwell and died in 1849. The article notes that ‘the missionary’ (Robert Barry Taylor) was indebted to Smith ‘for many personal favours’ – perhaps Taylor’s marriage at Camberwell was one of them.

Design of the Harpenden Chapel

The above website notes that the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) – the body that listed the building in 1982 – describes the chapel as: ‘an exact replica of the Harpenden chapel in England’. The website continues: ‘this cannot be corroborated at present as the Congregational Chapel at Harpenden was demolished. This does however seem unlikely as this Gothic Revival structure forms part of the specific architectural expression of this movement found in the drier parts of South Africa and is a direct result of materials and skill available; a localised vernacular’.

The Missionary Magazine article does not claim it to be a copy of a chapel in Harpenden. A comparison with the two contemporary chapels in Harpenden shows only a general similarity of appearance and floor plan. Neither of these Harpenden chapels had a tower.

The only other church in Harpenden at the time was St Nicholas, the parish church. This differs substantially in appearance and is not a ‘chapel’. The two chapels were:

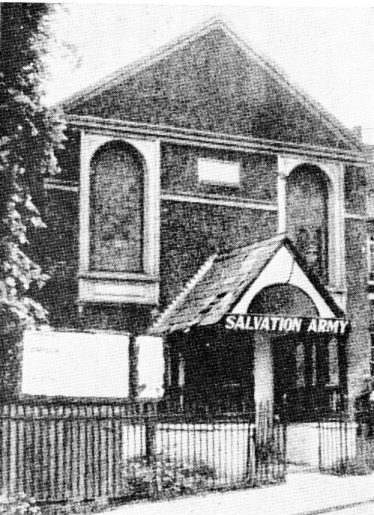

- The Independent (later Congregational) Chapel in Amenbury Lane, built in 1840. This still exists and at 48 x 20 feet is smaller than the Cradock building. The demolished chapel referred to above was in fact

- The Wesleyan Chapel in Leyton Road, built in 1839 and replaced in 1886 by a larger building.

The Independent Chapel, Amenbury Lane, built in 1840, became the Salvation Army citadel from 1908-1965. Credit: LHS archives

The first Wesleyan Chapel, Leyton Road, built in 1839. Credit: LHS archives – HC 157

The Harpenden Connection

It is reasonable to assume that Frederick Smith knew the ‘Rev. G B Johnson’ of Harpenden referred to in the article, although no clergyman of that name has been traced. Research eventually revealed that the benefactor was in fact the Rev. G T (George Terry) Johnson, the ‘B’ in the article being a misprint. The correct identity is given in articles printed in the Missionary Magazine & Chronicle, one of which is reproduced below.

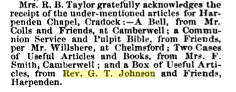

Missionary Magazine & Chronicle, July 1854, p 174. This volume has been scanned and reproduced online with no indication as to copyright ownership. Note the gift from Mrs F Smith of Camberwell and the bell from others at Camberwell.

The Rev. George Terry Johnson was the Minister of the Independent (later Congregationalist) Chapel in Amenbury Lane from 1845 to 1865. Frederick Smith’s influence may be seen in 1849; the Missionary Magazine for October of that year (page 549) records that ‘Mrs Johnson and friends’ of Harpenden had sent ‘a box of useful articles’ to the Rev. R B Taylor and Mrs Taylor in Cradock. Acknowledgements for further gift boxes were published in 1853, 1857 and 1858.

Emma Tatham’s Visit, 1855

In addition to the rather dry facts recorded above there is an insight into the life of the Rev. Johnson and his wife in Harpenden.

Emma Tatham. Credit: Frontispiece of ‘Memoirs of Emma Tatham’ by Benjamin Gregory – see notes below

In the summer of 1855(1) the prolific and much praised 25-year old poet Emma Tatham came to stay with her friend Mary Westbrook, the wife of the Minister of the Independent Chapel in Fish Street, Redbourn. Emma’s health was slowly deteriorating since a bout of whooping cough at the age of 16 and the visit was intended for her health.

Mary Westbrook wrote a memoir of Emma and tells of a visit to George Johnson’s house in Harpenden. From the Censuses of 1851 and 1861 we know that in 1855 he was 59 years old and his wife, Eliza, was 55. Mary Westbrook wrote that Mrs Johnson had gone blind and that George’s eyesight was failing.

George had expressed a wish to meet Emma after reading her book of verse ‘Pythagoras and Other Poems’. The walk took them through Rothamsted Park and after the visit Emma wrote a poem for him. The following verse gives an idea of her work:

“And when no more the lovely lanes of Redbourne bloom for me,

And when again I wander by the deep and distant sea,

Ah! Let thy prayer pursue me there – sigh that dear blessing then,

And this poor heart shall turn to thee, and hallow’d Harpenden.”

George had accompanied them through Rothamsted Park on their return and he refers to this walk in his poetic response:

“And now we tread the path of one, whose talents, wealth and lore

With persevering earnestness are given to explore

The secrets of true science: – may success crown his pains

And still increas’d fertility spread o’er our hills and plains.”

The Park at that date had been created from fields adjacent to Redbourn Lane (2). The walkers would have been aware of the brand-new Testimonial Laboratory at Rothamsted, construction of which had been completed by July 1855.

Soon after the visit Emma fell seriously ill and died in September. At her own request she was buried at the Chapel in Redbourn.

Where was George Johnson’s House?

Amenbury Lane, cottages next to the Chapel in 1981. Credit: LHS archives, from digitised slide

The 1851 Census shows the Johnsons living in the Bowling Alley (the area adjacent to the Skew Bridge, part of modern Southdown). From the order in which the Census was taken it is probable that they occupied the property that is now the Queen’s Head public house. In 1842 this was occupied by the Rev. J Davis, the first minister at the Amenbury Lane Chapel (3). The 1861 Census shows the Johnsons at the second cottage up Amenbury Lane from the chapel.

As the Bowling Alley was then a separate area from the village of Harpenden, Mrs Westbrook’s reference to Harpenden implies that they visited the house in Amenbury Lane.

More Rev. Johnsons and Dr Frederick Spackman

During the research for this article other Johnson connections to Harpenden were found. They are added here out of interest and as a guide to future researchers.

- The Rev. James Edward Johnson was a near-contemporary resident of Harpenden. In 1841 he occupied the premises now known as Wellington House in Leyton Road (4). The only other references to him traced are newspaper reports of his marriage in 1838 and the birth of a son in 1841. No information as to his precise affiliation and whether or not he had a ministry has been found.

- Dr Frederick Spackman came to Harpenden in 1851 with his second wife Caroline (daughter of the Rev. Robert Henry Johnson, Rector of Lutterworth). No connection between Caroline’s family and the Rev. James Edward Johnson has been found.

- Dr Spackman also had connections with Cape Province: his third wife, Eliza Jane Wright whom he married in 1862, was the daughter of the late Rev. W Wright of Graham’s Town. The Rev. W Wright is referred to as ‘a missionary to the coloured people of Cape Town’ in 1820 (5).

- Alice Spackman, daughter of Dr Spackman and Eliza, married one Daniel C R Greathead. Greathead was born at Cradock in 1850.

Notes

1 Taken from the following publications:

- Etchings and Pearls … , Mary Ann Westbrook, Judd & Glass, London, 1856, especially Chapter 10.

- Memoir of Emma Tatham, Benjamin Gregory, Hamilton & Co, London, 1859.

- The poetry generated by Emma’s visit contains many complimentary references to Harpenden and Redbourn. Scanned versions of both books and of Pythagoras and Other Poems may be found online.

2 Harpenden Tithe Awards and map, 1842.

3 Newsletter 126, August 2015 – http://www.harpenden-history.org.uk/page/burglary_at_the_bowling_alley_1846.

4 Harpenden Tithe Awards, plot 572

5 History of South Africa Since September 1795, G M Theal, Swan Sonnenschein & Co, 1908, p 348.

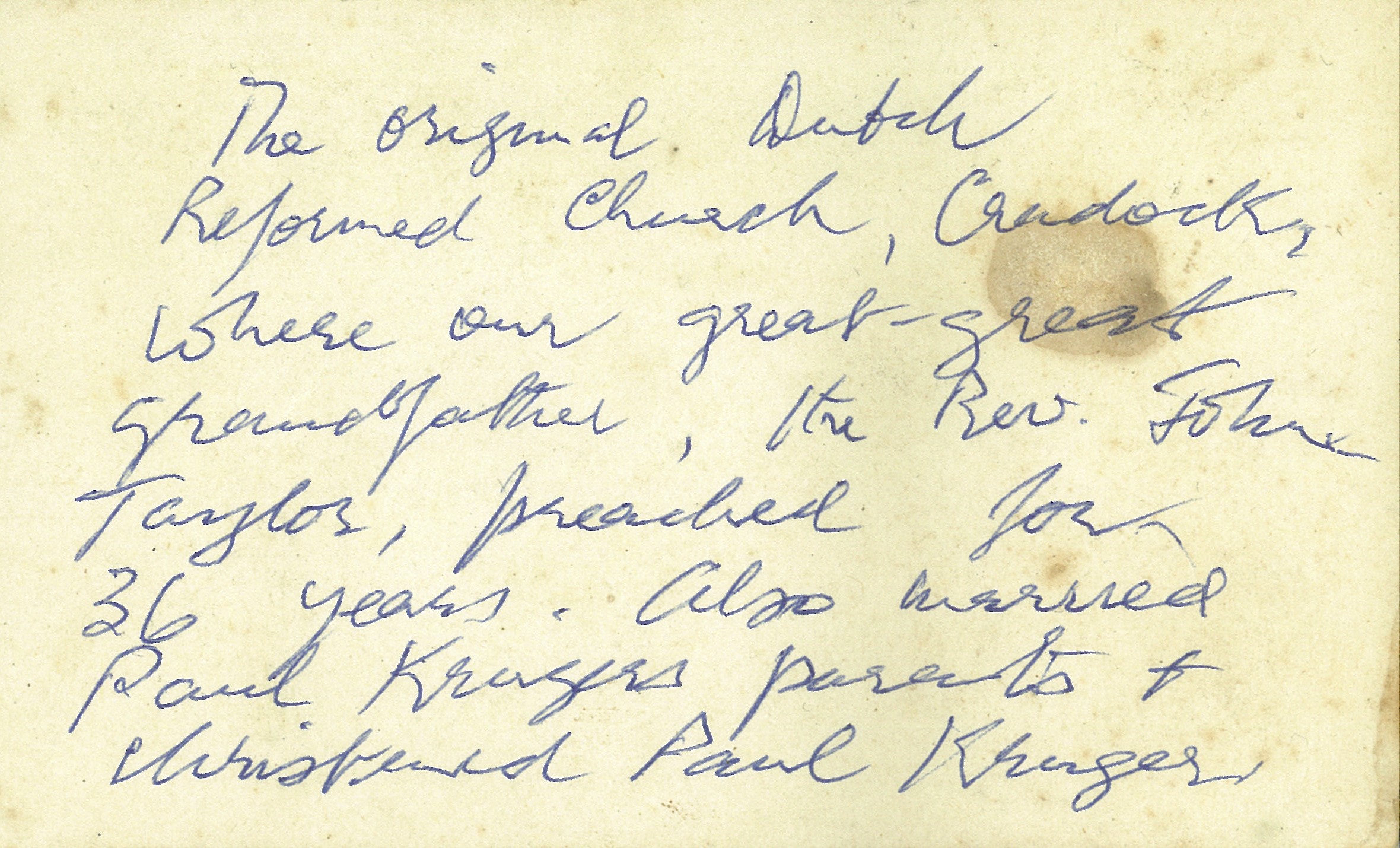

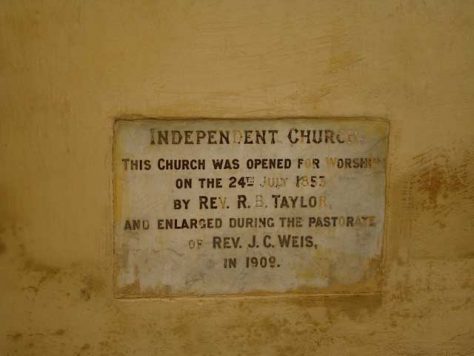

Photos of the Dutch Reformed Church at Craddock, sent by Trevor Armstrong,

Dutch Reformed church at Cradock

Reverse of the photo of original Dutch Reformed at Cradock

Comments about this page

Trevor Armstrong from Melbourne, Australia has contacted us:

“I’ve just read your article on the above with interest as the Rev. John Taylor is my great great great grandfather. I can see how people confused the two Taylor reverends. I have seen the Harpenden Church but also have a photograph of the original Dutch Reformed Church in Cradock if you would like a copy.”

Trevor has sent the photograph of the original Dutch Reformed Church in Cradock, dating from c1817, which is mentioned in the article. The note on the reverse states that Taylor not only baptised Paul Kruger at this church (mentioned in the article) but had also married his parents.

The photograph predates 1868 as the original Dutch Reformed Church was demolished and replaced by the current church in that year. It also raises the possibility that the design of the ‘Harpenden Chapel’ was based on the original Dutch Reformed Church, given the general similarity of both ‘as built’.

These images have been added at the foot of the page above.

Add a comment about this page