Harpenden Crown Post Office, c.1970, with entrance to the yard and sorting office. Credit: LHS archives – LHS 15615

I left St George’s in 1974 having already passed what would now be called a literary and numeracy test to become a Postal Officer (counter clerk). Several of my friends joined banks but the pay was better at the Post Office and I didn’t mind the longer hours. The Post Office was open between 9 and 5.30 each weekday, and between 9 and 4.30 on Saturdays. I trained at a training centre opposite St Pancras Station, then undertook a trial period in Remnant Street, off Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Harpenden was a Crown Post Office with its own Postmaster. Ivor Pigden was Postmaster when I joined. The Head Post Office was in St Albans where there were two Crown Offices – St Peter’s Street and Beaconsfield Road. To cover holiday or sickness leave, I worked at both of these offices.

At that time, The Post Office had two separate departments – Post Office and Post Office Telephones. Post Office vans were red; Telephone vans were yellow. They were either BMC or Commer vans – nothing as modern as an early Ford Transit!

Over the counter

The Post Office counter transacted a huge range of activity and our sliding counter drawers would be crammed with bits of paper all the time.

Postage stamps were a huge part of the business – normal stamps came as sheets of 200, high value ones (50p, £1, £2, and £5) came in 100s, as did special stamps of which there were six issues each year. The Philatelic Bureau took full advantage of these issues by providing special packs and first day covers. Keen philatelists would request specific blocks of stamps from within the sheets and would wince if we didn’t fold the perforations before tearing them. We also carried pre-stamped envelopes in two sizes, and pre-paid air letters (a sheet of very light paper which was gummed around the edges).

Nowadays the range of stamps is minimal since Post offices can print off labels with the correct postage. When the office was shut, there was a stamp machine that issued 2/- worth of stamps in a stitched booklet and another machine that dispensed 1d stamps from a roll. I seem to recall that a lot of Monday customers were those who’d lost their 2/- over the weekend since the books had a habit of jamming in damp weather.

We also carried a range of National Insurance stamps – these were half the size of postage stamps but had very high values.

Dealing in money

Postal orders were a popular way of sending money for goods through the post for those without bank accounts. These came in 5p increments from 5p to £1, and then £2, £5, and £10. In order not to unfairly compete with cheques (for which banks charged) POs had a fee payable, called poundage which added a few pence to the face value. Stamps could be stuck to postal orders to increase their value between the 5p increments. Postal Orders could be crossed to send through the post and when this was done they could only be paid into bank or National Savings accounts.

National Savings was also a part of the Post Office. We sold savings stamps, savings certificates, and premium bonds as part of this service. National Savings also had two kinds savings accounts which used passbooks. The regular account (in a blue book) allowed for money to be paid in and out like a modern day instant access account. We would hand-write deposits and withdrawals and re-balance the accounts.

The Investment Account (in a grey book) could be used for deposits, but withdrawals had to be made by sending off an application form. Each year, the books from both accounts could be posted off to National Savings for interest to be calculated and added.

As well as National Savings, The Post Office also owned a bank – National Girobank. It issued its own cheque books, paying in books, and another book for transferring money between Giro accounts. Utility companies used Girobank a lot. In addition, most Department of Social Security benefits (sickness, unemployment etc) would be made via a green coloured Girocheque.

Licences and allowances

National Savings was but one of a number of Government agencies to use the Post Office. Road Fund Licences were issued at the Post Office counter upon presentation of a certificate of insurance, valid MOT certificate where applicable, the old tax disc, a long form, and the correct fee. Licences could be bought for 4 months or 12.

The Post Office also issued dog licences (37.5 pence when I was there) as well as game and fishing licences.

The Passport Office allowed Crown offices to issue British Visitors Passports; a one-year travel permit for use within Europe, mainly. These were a bit of a nightmare when the counter was busy since processing them took at least ten minutes.

The Department for Health and Social Security used the Post Office to pay all old age pensions and family allowances. A large bundle of pension books and allowance books would arrive each day, to be filed alphabetically in drawers. The basic pension at the time was £10 a week for single people, £16 for a married couple. The Family allowance was 90p for the first child, £1.90 for the second, and increased by £1 per additional child. Pensions were paid out on Mondays and Thursdays, family allowances on Tuesdays. As counter staff we had to ensure we had enough cash to pay all these and would transfer money from the Postmaster’s safe to our own tills.

Franking machines

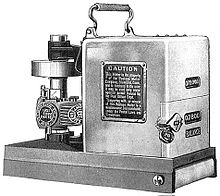

A Pitney-Bowes Model M franking machine c. 1920. Credit: Wikipedia, Postage Meter

Some businesses used franking machines to pay for their postage. There were several models made by companies such as Pitney Bowes and Roneo. These machines would be brought to the counter to have credit added to them – usually £200 at a time. They were fiddly machines which were locked by means of a braided wire onto which was fixed a lead seal.

Crediting them meant cutting this wire, moving cogs around within the machine, then re-wiring the lock and using a hand held press to squeeze the lead seal which had a crown impression as a result.

Public telephone boxes had cash boxes to take all the 2p and 10p coins used for making calls. These would be collected by postmen during the week and brought to the counter staff for their contents to be counted.

Telegrams, as a method of contacting people urgently had been supplanted by the telephone by the mid 70s, although we would occasionally send international ones and, of course, they were popular at wedding receptions to which they were sent by people unable to attend. On Saturday afternoons we made deliveries to receptions at the Moat House and Glen Eagles hotels.

The Harpenden counter supervisor was Arthur Sullivan who lived in Wheathampstead. My colleagues were Peggy Balme, Val Spink, Carmel McHugh, Ethel Holland, Mavis Treacher, and Sue Firmin.

In due course Mr Pigden retired and was replaced by Mr George Eve.

Whilst he was Postmaster, the Station Road office closed for major rebuilding works and the counter was housed in two ‘portacabins’ placed by the diagonal footpath on Leyton Green. It was a dreadful working environment during one of the hottest summers on record.

The hot and stuffy temporary Post Office, being installed on Leyton Green. Credit: LHS archives

From indoors to outdoors

The once a week balancing of our tills was something I didn’t enjoy and I spoke with Mr Eve about moving from the counter to be outdoor division – being a postman. It was a lower grade, but by becoming the local representative for the Union of Post Office Workers, I maintained my seniority from being at the counter due to the additional UPW responsibilities.

The sorting office was in the old Congregational Hall in Luton Road – the last building on the right towards Luton.

Old Post Office sorting office, Luton Road, before demolition in March 2016. Credit: Lindi Frith, Old Harpenden FB

The day would begin early by some of us being rostered to meet a train from St Pancras at around 4.45 am. We would load up a van with mail sacks and take them to the sorting office. A large van would also arrive from St Albans. One of these sacks would be a “REM sack” meaning it contained all the recorded delivery and registered envelopes which would be sorted by the Postman Higher Grade officers. The rest of us, all of us, would grab bundles of mail and sit on swing-out seats in front of sorting frames of different sizes to accommodate small or large letters. Packets were sorted into sacks which hung from frames. Harpenden had about 36 rounds at the time. From time to time we had to sit accuracy as well as speed tests for this work. Sorting small envelopes was the quickest task; we’d probably each sort 150 per minute of these.

Huge volumes of mail

It’s hard to comprehend, now, just how much mail there used to be. For most rounds, one sack wasn’t enough so we’d set off with two. Any more than that would require either a return trip to the sorting office or, preferably, a word in the ear of a driver who would drop off a bag under a bush in someone’s front garden along the route.

Some rounds were compact, others straggled in long lines between them.

One of the rounds in my section, “Park” started at the bottom of Park Hill, then Roundwood Park, Park Rise, Harpenden Rise, and ended at the bottom of Park Mount – very close to its start. That was easy.

Another of my rounds was called “Bowers” which started at the bottom of Vaughan Road, then took in Victoria Road, Bowers Way, Sun Lane, Pigeonwick, Ox Lane, Fallows Green, Oulton Rise and ended in Wroxham Way – a very long way from its beginning.

The third round of my section started in St Albans Road (a little known address which is the cottages at the rear of The Silver Cup ) then wound its way up West Common to Hatching Green an on to West Common Way, Oakfield Road, Oakhurst Avenue, Oak Way, Dellcroft, The Uplands, the Beeson End development and ending up at Maple Cottages.

Sometimes, due to sickness or annual leave, we would have to deliver two rounds.

Bills for rates, electricity, gas, telephone, television licences, and water rates would all arrive by post. Every house would be visited when this happened. Private letters were still very common, and during the summer we’d deliver hundreds of postcards.

Once the mail had been sorted into rounds, we had our tea break – at around 5.30 am. Then we collected from the inbound frames all the mail for our own rounds. At Luton Road these frames were similar to the inbound frames and we’d first sort our rounds into road order. When that was done, we’d take each bundle of mail and sort it numerically before tying the mail into bundles and filling our sacks. For some roads it was more expedient to deliver along one side and come back along the other, but sometimes it was better to criss-cross the road delivering odd and even numbers alternately.

We would all leave at 6.45 on our bicycles. A few rounds were delivered by drivers using vans. Kinsbourne Green was served this way, as was Ayres End and Mackerye End. The High Street delivery used a handcart. (I do remember as a boy that this was an electric vehicle).

The first delivery was usually finished by 9 o’clock by which time we would be very widely spread around the town – perhaps at the top of Pickford Hill, or at Beeson End Farm. Our last job was to empty any pillar boxes on our round. This mail would be emptied out onto a table in the sorting office and we’d extract any local items which would be sorted to form the 2nd delivery along with another van load of mail that would have arrived from St Albans.

After a cup of tea we’d set off again. We’d almost always be back by midday.

Parcels were delivered separately. The Post Office ran what is now known as ParcelForce. Many of these parcels were large home-shopping catalogues from Grattan, Littlewoods, and Freemans.

Overtime was available in the afternoons from about 4pm to 6.30. These duties would include collecting sacks of mail from local businesses by van, and emptying pillar boxes – as well as clearing all the mail and parcels from the Post Office counter in Station Road as well as the sub Post Offices. All of this mail would be driven over to the St Albans Sorting Office in Pageant Road for outward sorting – something Harpenden didn’t do.

Every day, one person would have the job of bicycle maintenance – mending punctures or replacing broken chains.

Once a year it fell to the sorting office to deliver telephone directories and Yellow Pages. These were huge books, delivered to every house with a telephone. There was little by way of ‘junk mail’ at the time; the closest we came was delivering thousands of “Readers Digest” prize notifications.

The Luton Road sorting office closed in 1976 when the new facility was opened above the counter at 25 Station Road.

Forty years later

Forty years later, neither the Post Office counters nor the sorting offices transact the businesses they did. Crown Post Offices are being sold off for their development potential and now reside within newsagents or other local shops, many of which have longer operating hours. From the 1980s successive governments took contracts away from the Post Office counter. Back in the 1970s it was illegal for anyone other than the Post Office to sell postage stamps.

The drop in the volume of letters through sorting offices has been partially replaced by their being used as the preferred delivery system for on-line purchases which has resulted in daily mail deliveries being more packet oriented. Delivery Officers, as they’re now called, use small vans and trolleys instead of bicycles and sacks.

Comments about this page

I worked for Royal Mail from 1977 to 2010 in Sheffield as postman; on the counter and in administration and much of what Peter Bigg says is very familiar to my experiences.

I can remember delivering after a snowfall of about a foot deep in 1977. It took me an hour to carry 2 bags of mail to my starting point and then about 4 hours to complete the delivery, an elderly lady took pity on me and toasted me a crumpet and gave me a cup of tea.’

Add a comment about this page