Professional body snatchers, known as ‘resurrection men’. Credit: mad doctor mcdowell.com

A need for bodies

Concern about grave robbing in England was in evidence as early as the 1600s, as indicated by the epitaph on William Shakespeare’s tombstone:

GOOD FREND FOR IESVS SAKE FORBEARE

TO DIGG THE DVST ENCLOASED HEARE

BLESTE BE Ye MAN Yt SPARES THES STONES

AND CVRST BE HE Yt MOVES MY BONES

For surgeons needing detailed knowledge of anatomy, real bodies have always been the best tool. From the mid-eighteenth century, the only bodies legally available for dissection were those of executed criminals and the elite guilds of surgeons and physicians were entitled to no more than six each year

William Hogarth:The Four Stages of Cruelty: The Reward of Cruelty (1751)

As demand for bodies far outstripped legal availability, the gruesome practice of grave-robbing became a lucrative industry. Respectable surgeons were forced into unsavoury agreements with ‘resurrection men’, who scoured burial grounds at night for freshly dug graves and ‘resurrected’ newly-buried bodies to sell to medical and anatomy schools. Financial inducements were such that the illegal trade of body snatching continued to grow.

Resurrection men

Corpses were found through a network of informers – sextons, gravediggers, undertakers and local officials, who each connived to take a cut of the proceeds. Resurrection men usually dug a hole down to one end of the coffin sometimes using a quieter, wooden spade. A sound-deadening sack was placed over the lid, which was then lifted. The weight of soil on the remainder of the lid snapped the wood, enabling the robbers to hoist the body out. The corpse was then stripped of its clothing, tied up, and placed into a sack. The entire process could be completed within thirty minutes. Corpses of paupers were easier to access, as they were often buried in mass graves, left open to the environment until filled.

The activities of resurrection men gave rise to public fear and revulsion. There was a strong belief that in order to stand a chance of redemption, a corpse should be left intact, undisturbed by desecration. For most people being sold for dissection was a shameful fate and many saw dissection as equivalent to damnation.

Body snatching in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire’s close proximity to London made it an excellent place for body snatchers to do their work and they were particularly active there during the 1820s. Corpses were taken from isolated country churchyards and towns such as Hitchin, Watford and Luton. Deals were done at inns and bodies bound for anatomy schools in London were hidden in sacks and smuggled onto coaches.

Harpenden labourers suspect foul play

On 15 November 1823 at about five o’clock in the morning James Finder, a labourer from Harpenden, set out for work along Staker’s Lane (renamed Station Road in 1892). When he reached the Harpenden Road to St Albans he noticed a cart being driven along and a man walking behind it. As he followed it down the road an offensive smell came towards him from the cart. He thought it was from a putrid corpse and suspected those with the cart were resurrection men.

James Finder was soon overtaken on the road by his brother, Thomas, and confided to him his suspicions. They both worked for Mr Fowler (possibly a member of the family of builders and brick makers in St Albans) so they increased their pace until they arrived at their workplace. When the cart arrived there, Mr Fowler, a ‘gentleman’, told the men to stop. They refused so James Finder and others took hold of the horse and the cart was searched. The corpse of a very elderly man was found in a sack hidden under a quantity of straw. The driver of the cart, John Jerome, and his companion, John Holloway, both from East London, were arrested and James Finder helped take the corpse to St Peter’s workhouse in St Albans.

Arrest and preliminary hearing

On Saturday 22 November the weekly meeting of the Magistrates of the Borough of St Albans and the County of Hertford, the Earl of Verulam, Sir William Domville, Rev Dr Bowen, Mr Gape, Mr Brown (Mayor) and Mr. Kinder, took place in Hertford Town Hall. Jerome, a labourer from 3 Kingsland Road, Shoreditch and Holloway, a gardener from Gloucester Place, Hackney,were charged with disinterring and carrying away a male corpse from the churchyard in the parish of Luton in Bedfordshire on the night of the 14th or the morning of the 15th November.

William Yardley, a farmer and churchwarden of the parish of Luton, had just been informed by John Deacon, keeper of the St Albans House of Correction, about the exhumation of the corpse and they were there together at Hertford Town Hall to prosecute the investigation.

At this preliminary hearing, Thomas Foster, the elderly sexton of the parish of Luton, affirmed that the grave was that of William Gilman, buried on the 2 November, 13 days before the grave robbery. He had since seen the corpse in St Peter’s workhouse and knew it to be that of the late William Gilman, whom he had known for more than 45 years. He informed those present that the grave was not much disturbed but the shroud and coffin were left behind. The coffin had been forced open at the shoulders, the lid taken entirely off and all the screws taken out. He was sure he had never seen the prisoners before nor ever received any money from them.

Thomas Porter, the master of St Peter’s workhouse, stated that the corpse had been brought to the workhouse at about eight o’clock in the morning. Asked if he had anything to say, the prisoner, Jerome, said he would reserve his defence and Holloway remained silent. Jerome had borrowed the horse in London from William Clark of Busby Street, Spitalfield Square and hired the cart from John Phillips of Horseferry Road, whose name was on the off-side. Jerome and Holloway had travelled about 30 miles to commit the crime.

James and Thomas Finder, as witnesses, stated that they had seen Jerome and Holloway in the area three or four days previous to the body snatching, driving a very heavily laden cart and the smell then had been offensive. The repetition of this circumstance had prompted them to act as they had done. William Yardley, the churchwarden from Luton, said the witnesses’ conduct should not go unrewarded.

Detention and committal

Mr Brown, the Mayor of St Albans, directed the prisoners to be securely conveyed to the St Albans House of Correction and they were committed for trial at the next quarter sessions. He particularly cautioned the constables to protect the men from the mob. The court room, which was very spacious, was extremely crowded and the prisoners were loudly jeered on their way from the Town Hall.

The Sessions Records of the Liberty of St Albans Division for the Epiphany Session in January 1824 state that Jerome and Holloway were ordered to be transferred to Bedford Gaol and then tried at the next Assizes held in that county. They arrived at Bedford Gaol on 20 January 1824.

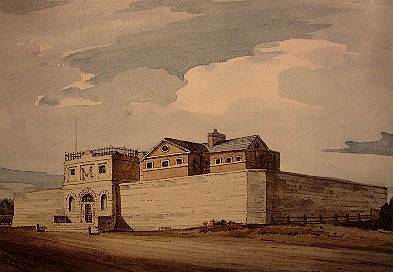

Bedford County Gaol c1820. Credit: Watercolour by T Fisher (gallery.e2bn.org)

The Registers of Bedford Gaol show their conviction at the Lent Assizes in 1824. Jerome, aged 25, 5′ 6″ in height with dark brown hair and a ruddy complexion and Holloway, aged 45, of similar height with dark hair and complexion, were both committed for three months each for robbing a grave.

The regime at Bedford Gaol included a silence system enforced with great severity, with wooden partitions placed between any two prisoners at work on the treadmill. Exercise was allowed in the yards and meals were taken in the cells. During their sentence Holloway behaved in an ‘orderly’ manner and Jerome’s conduct was described as ’indifferent’. They were released on 6 June 1824, having spent a total of 6 months there.

The end of resurrection men

Eight years later, the controversial Anatomy Act of 1832 ruled that bodies ‘unclaimed’ or ‘friendless’ could be given up for dissection. This gave doctors and students legal access to unclaimed bodies from prisons or workhouses but it was clear that the burden would fall on the poor. The Act was unpopular and proved difficult to enforce. Parishes refused to hand over bodies from their workhouses, officials made private deals with local hospitals for their own personal gain and mistakes with bodies could be blamed on ‘clerical errors’. It is estimated that during the first 100 years of the Act’s operation 57,000 corpses were supplied, 99.5% from workhouses, asylums and hospitals. The burden was indeed borne by the poorest in the local communities. The Act left a long legacy of fear that falling into poverty would mean the State could claim a body after death. However, the Act was successful in putting body snatchers out of business and marked the beginning of the end of activities of resurrection men such as John Jerome and John Holloway.

Sources:

- The Times, 25 Nov 1823, Times Digital Archive.

- Sessions Records of the Liberty of St Albans Division, 1770-1840, Volume 4, Epiphany Sessions, January 1824.

- Bedford Gaol Register, Bedfordshire Archives and Records Service.

- The Report of the Committee of the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline,1832.

- Victoria County History, part 25 (Bedfordshire edit)

- Louise Fowler & Natasha Powers, Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men, 2014.

- Ruth Richardson, Death, Dissection, and the Destitute, 1987.

- Julia Bess Frank, ‘Body Snatching: A Grave Medical Problem’, The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine (1976)

No Comments

Add a comment about this page